I flew to Tibet in late August 1988 to cover the first U.S. Senate delegation to visit “the rooftop of the world.”

Lhasa, at 12,000 feet the Tibetan capital and traditional home of the Dalai Lamas, was under strict control.

Following protests that turned violent in late 1987 and again in March of 1988, the Chinese government had begun to invite selected visitors in to show that “social order had been restored.”

I had been waiting in Chengdu, the jumping-off place for Tibet, nearly 1,500 miles east of Lhasa, to see if I could get on the senators’ plane and accompany them to the Tibetan capital.

At almost the last minute, as I sat with delegation members in a Chengdu hotel, a Chinese foreign ministry official told me that I could go.

I didn’t expect to learn much during the three-day guided tour being offered to the three senators. The government seemed to have scripted every move, leaving nothing to chance.

I was there as bureau chief for The Washington Post in Beijing. Two western television networks were allowed in as well. The delegation of three senators was led by Sen. Patrick J. Leahy, a Democrat from Vermont.

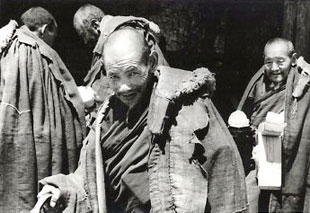

Lhasa was now tightly controlled. Someone told us that the beggars and pilgrims who usually surrounded the Jokhang Temple, often described as the spiritual heart of Lhasa, had been replaced by state security officers in disguise.

To me, the Tibetan pilgrims looked real enough but I thought I detected something phony about the beggars.

Once we began to walk through the Jokhang, however, controls began to fray.

While foreign ministry officials focused on the visiting senators, a monk managed to draw me and a Senate aide into a darkened room.

There he showed us a blood-stained monk’s robe that he said belonged to a monk who had been beaten and killed by the police during the rioting in March. Other monks whispered stories of repression and torture.

It turned out that the senators’ staff members had done their homework. This enabled Sen. Leahy and the two senators who traveled with him to ask sharp questions of officials of the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) government.

Leahy said that a number of Tibetans told delegation members and staff that monks and laymen detained during the earlier rioting had been tortured and denied basic human rights.

Leahy was accompanied on his trip to Tibet by Senators Thomas A. Dashchle, a Democrat, and Robert T. Stafford, a Republican.

In a meeting with the three senators that was open to the visiting reporters, Mao Rubo, vice chairman of the TAR government, said that he and the senators held “differing views as to the meaning of human rights.”

I returned to the Jokhang, where a monk emerged from a dark corner to say briefly, before disappearing, “We want the Chinese out of here.”

I then had a brief conversation with another Jokhang monk with whom I played devil’s advocate.

I said that in some regards he and his brothers and sisters were probably better off in material ways as a result of Chinese economic reforms, new roads, and other “modernization” efforts.

Inviting me to accompany him past a row of prayer wheels that he spun as we walked, the monk said that, yes, in some ways his family’s lives had improved. But, he said, he did not feel comfortable with the growing Chinese presence in Lhasa.

He regarded the discos and pool tables that seemed to be cropping up everywhere as a corrupting influence on Tibetan youths.

“Lhasa is surrounded by pool tables,” he complained.

At Sera, a 15th century monastery north of Lhasa, I saw dozens of monks chanting while others engaged in debates.

One young monk, standing at the center of a monastery courtyard, posed questions to another, seated monk. The monk asking questions dramatically slapped one hand down on the other. He circled his opponent. He stamped his foot.

At one point, the monk being tested faltered and misspoke, bringing gales of laughter from several dozen monks sitting in a semi-circle around the disputants.

It was obvious that this was not just a key part of Tibetan monastic education.

It was also a form of entertainment.

As I wandered about the monastery, a young man sidled up to me.

“Would you like to meet a political prisoner?” he asked.

I had to decide quickly if this was a trap set by the informers said to be everywhere in Lhasa.

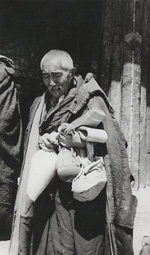

I decided to take a chance and followed the young man to a monastery cubicle. There a middle-aged, maroon-robed monk sat next to pictures of the exiled Dalai Lama.

The monk rebutted Chinese denials of torture against demonstrators, saying that prisoners arrested during and after the anti-Chinese demonstrations and riots of the previous year had been severely mistreated.

The monk said that the police had stunned him with electric cattle prods when he was arrested during a demonstration in early March 1988. He said that he had not participated in the demonstration but was caught up with a group of monks who were arrested.

The monk also said that guards at a detention center had beaten him with their fists but that he was much less harshly treated than some other prisoners.

Years before as a reporter in Vietnam, I had been lied to by a South Vietnamese student who claimed to have been tortured by government police.

I had unintentionally published a lie, and I never wanted to get burned like that again.

But I had good reason to believe the Tibetan monk’s story.

Detailed statements by other Tibetans who had been released from prison, transcripts of lengthy interviews with former prisoners, and information gathered by western human rights organizations indicated that in fact police guards routinely tortured Tibetans who were accused of engaging in anti-Chinese demonstrations.