HONG KONG—Chinese journalists who reported claims that a security guard raped a petitioner from Anhui province in one of Beijing's "black jails" have been investigated by authorities, as the woman's family calls for a full inquiry.

Journalists Chao Getu and Yang Jibin were not currently at work, their colleagues at the Guangzhou-based cutting-edge Southern Weekend newspaper said.

"They made the reporters write an examination report," said an employee who answered the phone in the newspaper's editorial department.

"Probably the government thought there was a problem, because it touched on human rights."

"They're not working any shifts right now," he added.

Meanwhile, Anhui petitioner Li Ruirui has been sent to a psychiatric institution for "treatment" by the municipal authorities in her hometown of Jieshi after she alleged that a security guard at an impromptu detention center set up in Beijing's southern Fengtai district had raped her, Li's relatives said.

Li, 21, had gone to a local police station to report the rape, which she said left blood on the bed where she was attacked by a security guard at 2 a.m. on the morning of Aug. 5.

The detention center was in Fengtai's Juyuan Hotel, where officials frequently detain people from outside the capital who travel there to complain about them.

Li said she was raped by a hired security guard known as "Xiao Qiang," who was well-known to staff there.

Complaint lodged

The case was being handled by the Yangqiao police station in Fengtai.

Civil rights activist Zhao Lianhai said he had lodged a complaint on behalf of Li at the Beijing municipal police department last week, but was detained as soon as he did so.

"We are all here at the east gate of the police station, and we are all discussing the topic thoroughly. Call me again in half an hour," he said.

Thirty minutes later his telephone was switched off.

Zhao later sent a text message saying he had been detained at the Dongjiaomin police station in the capital and calling on the media to take photographs of the remaining evidence before it disappeared.

An employee who answered the phone at the Juyuan Hotel said the police had told them Li Ruirui's claims were untrue.

"The police at that station told me that these claims were false," the receptionist said.

"You can ask them. We don't know what happened."

An officer who answered the phone at the Dongjiaomin Alley police station declined to answer questions about Zhao and his companions.

Lawyer sent

"You will have to ask the external relations department of the police station. We aren't allowed to answer reporters' questions."

Meanwhile, Li's uncle, Wang Zhongcheng, said officials had also sent a lawyer to visit them to ask if there was anything the family needed.

"She doesn't have a mental illness," Wang said.

"Today they sent a municipal official to visit us and to ask us whether we had an opinion, or any requests."

"They asked us to write them down, and they took the papers relevant to her case away."

He called on the authorities to investigate the claims properly.

"They should treat serious allegations seriously," Wang said.

"They should pursue a criminal investigation in accordance with the law."

Hangzhou-based journalist and Web author Zan Aizong said the authorities seem anxious to prevent further information from leaking to the public, because of the damage it would do to the government's image.

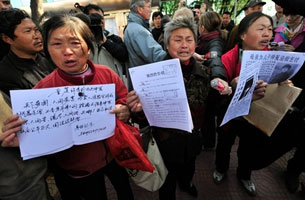

"There are a lot of petitioners who come to Beijing, and they are locked up in 'black jails,'" Zan said.

"Reports about this don't get out, because the Central Propaganda Department has cut them off at source," he said.

Open letter

"Most media organizations wouldn't dare to cover such an explosive story."

Zan said he had penned an open letter to Chinese premier Wen Jiabao, asking him to take a personal interest in Li Ruirui's allegations.

In it, he calls on Wen to wake up to the plight of China's millions of ordinary people who try to make complaints about official wrongdoing across China.

"You are the prime minister," Zan wrote in the letter posted on his Web site.

"You can't ignore China's petitioners forever."

China's official complaints system, set up five decades ago to serve as a bridge between the ruling Communist Party and the people, seldom resolves anything, sparking instead further detentions, beatings, and harassment of those who dare to complain, petitioners and social activists say.

Local government officials are increasingly using unofficial detention centers, known as "black jails," as a way to control the millions of disgruntled people trying to get to Beijing to make complaints, often related to land deals, corruption, and forced evictions.

Chinese citizens trying to pursue long-running complaints against the government can also find themselves committed to psychiatric hospitals and force-fed medication to stop them from "causing trouble," petitioners and officials have said.

Original reporting in Mandarin by Qiao Long. Mandarin service director: Jennifer Chou. Translated and written for the Web in English by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Sarah Jackson-Han.