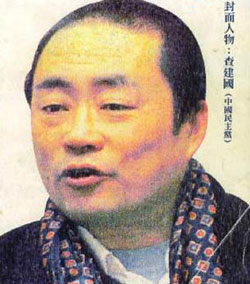

"I told them when they let me go that I would continue to appeal my

sentence because I felt that this was a miscarriage of justice," Zha said

in his first public interview since his release on Saturday.

"That is my right as a citizen. So I intend to continue to pursue this as

a wrong case against me, and appeal to have my name cleared and to have the

case against me overturned."

Zha, who served a nine-year jail term for helping to found the China Democracy

Party (CDP) in 1998, during a period of relative political openness known as

the "second Beijing spring," said police had also set restrictions on

him because his sentence included two years'

deprivation of political rights.

"The day they let me go, they dispatched cars from the city and district Public Security bureaux to pick me up from jail and take me to the local

police station," Zha said.

"Once inside the police station, they issued me with a warning, which they

videotaped. They told me that during the period of deprivation of my political

rights that I wasn't allowed to give any interviews to foreign reporters, and

that if I wanted to go anywhere I had to ask for leave from them," he

added.

Different treatment

But Zha, one of the first people to serve as chairman of the now-banned CDP and

deputy head of the party's Beijing and Tianjin chapter, said he had already

told the authorities back in the prison that he wouldn't recognize such

restrictions.

"I told them I didn't accept any of the curbs they had in mind for me, and that

I wouldn't comply with any of it," he said. "Of course, if they

wanted to take steps to keep foreign journalists away from me then that would

be up to them to see if they could."

He described his time in prison as "an opportunity" and a form of

retreat, and "an education like no other."

He said his democratic ideals were unaffected by his time inside, where he was

treated worse than fellow prisoners because he had refused to confess.

"The authorities treat you very differently if you have never confessed to your crime, as if you are not like the other inmates, and I had never confessed to my crime," Zha said, who said he was simply acting on the rights of citizens as enshrined in China's Constitution.

"For example, if some of the other inmates were allowed to meet up and eat

a meal with their family every two or three months or so, you would not be

allowed to eat with them; other inmates were also allowed to phone home once a

month but I wasn't. Other inmates were given parole, but I wasn't. That's the

way it was," he said.

UN rights covenant

He said he and fellow activists back in 1998 set up the CDP because they wanted

to test out China's signing of the United Nations covenant on civil and

political rights.

But by December 1998, three key figures of the movement—Xu Wenli, Wang Youcai,

and Qin Yongmin—were being tried and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

CDP branches and committees had been set up in more than 20 provinces, and the

arrest and jailing of CDP supporters continued well into 2000. More than 30

current or former CDP members remain in prison or in reeducation-through-labor

camps.

Original reporting in Mandarin by Xin Yu.

Translated and written for the Web in English by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by

Mandarin service director Jennifer Chou and Sarah Jackson-Han.