HONG KONG—China's official complaints system, set up five decades ago to serve as a bridge between the ruling Communist Party and the people, seldom resolves anything, sparking instead further detentions, beatings, and harassment of those who dare to complain, petitioners and social activists say.

Chen Mingguang was a restaurateur in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, but his restaurant was forcibly demolished in 2004.

After a local court turned down his lawsuit to appeal the amount of compensation, he began to petition the central government in Beijing in 2007.

Since then, Chen has been detained four times.

"In March of last year, I was brought back from Beijing and locked up in a ‘legal education class’ in Wuhan,” he said. "All rooms are sealed with iron-clad doors, with bars on the windows."

Many of the petitioners think that officials in their hometown are lawless."

Liao Yiwu, author

"On April 10, I tried to hang myself from the window, but I was rescued by guards. Then they released me after forcing me to promise I wouldn't petition in Beijing again," Chen said.

Chen's tale isn't uncommon.

Beatings, detentions

Since passing a new set of regulations governing petitioners in 2005, the authorities have developed an efficient system for dealing with those who complain, dispatching officials to provincial capitals and to Beijing from local governments, who detain, beat, and otherwise harass petitioners in a bid to make them drop their cases.

Nantong city petitioner Zhang Hua said she tried to petition the Supreme Court in Beijing last May and was detained by four unidentified men.

"Suddenly four unknown men dashed to me and held me. I yelled for help, but it was no use," Zhang said.

"They rushed me to a vehicle parked at the roadside. When the door was opened I was surprised to see the chief of our city’s letter and visits bureau right there in the car."

"I was pushed in."

The police detained her for three days at the Nantong representative office in Beijing before bringing her back to Nantong city and releasing her.

The 2005 regulations on petitioners order governments at all levels to "effectively handle letters and visits by conscientiously dealing with letters, receiving visitors, heeding people’s comments, suggestions, and complaints, and accepting their supervision, so that the people’s interests are best served."

"No organization or individual may retaliate against letter-writers or visitors," it adds in the following clause.

Call for reform

In an attempt to put pressure on the government over cases such as Chen's and Zhang's, Beijing Institute of Technology professor Hu Xingdou called in an open letter earlier this month to the National People’s Congress and the State Council for reform to the petitioning system.

"The ultimate solution I think is overall reform, a reform which can guide China towards democracy and rule of law," Hu said.

Direct personal appeals to high-ranking government officials became common during the Qing dynasty (1644-1912), with petitioners frequently seen banging drums outside government offices, or yamen, in the absence of a formal judicial system.

The contemporary "letters and visits" system was formally established in 1951 and reinstated during the 1980s following the large number of appeals against summary verdicts handed down during the political turmoil of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

China says it receives between 3 million and 4 million complaints in the form of "letters and visits" annually, although that number peaked at 12.72 million in 2003.

Still more cases are turned away for administrative reasons, for example, if they are already the subject of a lawsuit.

Liao Yiwu, author of a book about the phenomenon titled "Petition Villages in China," said hope of redress was the main factor driving people to petition the authorities again and again, sometimes for decades.

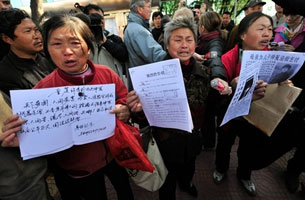

Thousands enter capital

"Many of the petitioners think that officials in their hometown are lawless," Liao said.

"They think the central government might treat them differently."

Petitioner numbers in the capital were estimated at around 1,010 during a 2007 survey conducted by petitioners themselves.

A semi-official survey by the prestigious Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) put the number of petitioners in Beijing at around 2,000, with as many as 10,000 entering the capital during the annual parliamentary sessions in March.

Of the 1,010 surveyed by petitioners, 470 reported being beaten by police or officials and 420 were detained or sent to labor camp, while more than 30 were incarcerated in mental hospitals.

Wu Youming, a former police officer turned whistle-blower in the central city of Huangshi, said controlling petitioners was part of his job.

"I was personally involved in many actions to stop petitioners, including in railway stations or in the homes of petitioners," Wu said.

"As far as I could see, most petitioners are law-abiding citizens. The police actions were illegal because no Chinese law allows anyone to limit the freedom of law-abiding citizens," he said.

Original reporting in Mandarin by An Pei. Mandarin service director: Jennifer Chou. Translated by Chen Ping. Written for the Web in English by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Sarah Jackson-Han.