Despite pledges to fight rising prices, China's government is fueling inflation by promising faster pay hikes over the next five years, experts say.

As food and housing costs grow, the government is feeling the pressure to meet wage demands and keep its cities affordable for workers and the rising middle class.

But provisions of the government's 12th Five-Year Plan are raising concerns that its promises of steady pay increases will only drive prices up.

On March 11, the official English-language China Daily reported that 29 of China's 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities have already announced plans to match pay raises to gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates in 2011-2015.

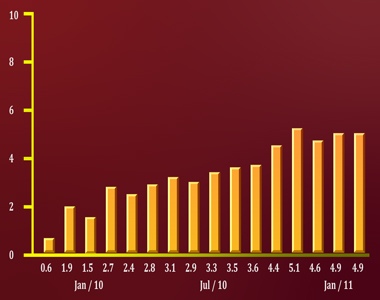

The plans are sparking concerns because the central government has targeted an average annual GDP growth rate of 7 percent through 2015, which is even greater than consumer price inflation (CPI), officially at 4.9 percent in February.

On March 5, Premier Wen Jiabao told the National People's Congress (NPC) that the government would increase urban and rural incomes at the same 7-percent rate for the five-year period.

Linking wage hikes to inflation would be bad enough. The practice known as "indexing" can set off a "ratchet" reaction as wages and prices push each other continually higher.

Price hikes seen

In China's case, the plan could be worse because wage hikes would be even higher than inflation, encouraging greater price increases. Provinces also regularly overshoot the central government's GDP targets, setting the stage for even bigger wage demands.

"If this becomes an accepted policy in China, it's pretty dangerous," said Gary Hufbauer, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

"This is the classic wage-price spiral," he said. "Prices go up, wages follow, prices go up some more and there's no limit to the process, so you have to break it at some point or you end up in higher inflation."

While the effects may take time to emerge, the plans appear to be trending in the wrong direction.

Five provinces have already announced plans to raise incomes even more than economic growth, and it is unclear whether they mean the central government's conservative 7- percent target, actual GDP, or their own regional rates.

Over the past five years, China's annual GDP growth averaged 11.2 percent, topping the official target of 7.5 percent, according to official data.

The fear is that the promises from the central government and the provinces will create inflationary expectations for both prices and pay.

"People will expect wages to go up, and there will be a lot of focus on every quarter's GDP growth, because that means a wage boost," said Hufbauer. "You can see the spiral effect of all that."

Risk of unrest

"People who are affected by inflation put pressure on the government to raise their wages, because otherwise they lose out. So the government raises their wages, which only contributes to further inflation," he said.

'Two things at once'

Although China has suffered from major bouts of inflation in the past, it may face special pressures from last year's soaring property market, which priced millions of rural workers out of the cities.

Dittmer said China has been trying to deal with labor shortages by meeting wage demands, although some officials have argued that the problems mainly affect coastal production centers.

In March, the southern city of Shenzhen said it would boost its minimum wage by 20 percent after Shanghai announced a 14-percent increase starting April 1.

Dittmer said the concern is that China will run into the phenomenon known as the "Lewisian turning point," an economic term named for Nobel laureate Arthur Lewis, who first drew the link between labor shortages, urbanization, and inflation in 1954.

Under the theory, wages start to rise when the supply of surplus labor moving from the country to cities is used up. It is unclear whether China will reach such a turning point, but the conditions have put the government on guard.

Dittmer said the government has taken economic steps to control inflation, but it seems to be pulling in the opposite direction with its wage promises.

"They're trying to do two things at once. They're trying to keep the factories humming and respond to the decline in labor supply, and cut inflation by raising interest rates and monetary controls," he said.